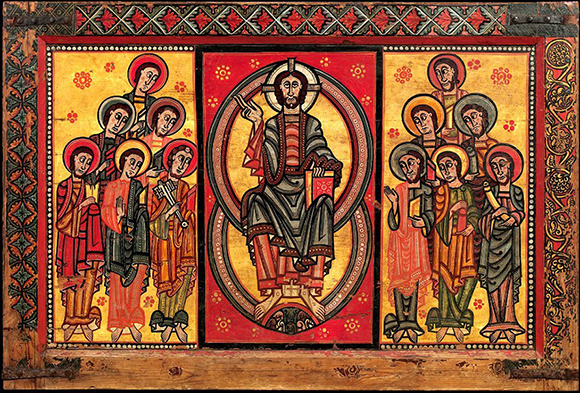

The O Antiphons (also known as the Great Advent Antiphons or Great Os) are sung verses used in evening prayer during the last seven days of Advent (December 17-23) at the beginning and end of the Magnificat, a hymn of praise spoken by Mary. Rendered in order, in Latin and English, the O antiphons are: O Sapientia (O Wisdom), O Adonai (O Lord), O Radix Jesse (O Root of Jesse), O Clavis Davidica (O Key of David), O Oriens (O Radiant Dawn), O Rex Gentium (O King of Nations), and O Emmanuel (O God-with-us).

As an acrostic, the Latin version reads SARCORE, reversed as ero cras (“I will be tomorrow.”) As the Antiphons are traditionally chanted through 23, Jesus is literally born “tomorrow” at the chant's conclusion. Medieval writers loved acrostics. Hebrew psalmists used them in the Bible too.

The O Antiphons have been around at least since the 8th century. Early versions have as many as 12 antiphons, including some for Jerusalem, the Trinity, Gabriel, and the Virgin. When Pope Pius V standardized the liturgy after the Reformation, the O Antiphons were definitively set at seven.

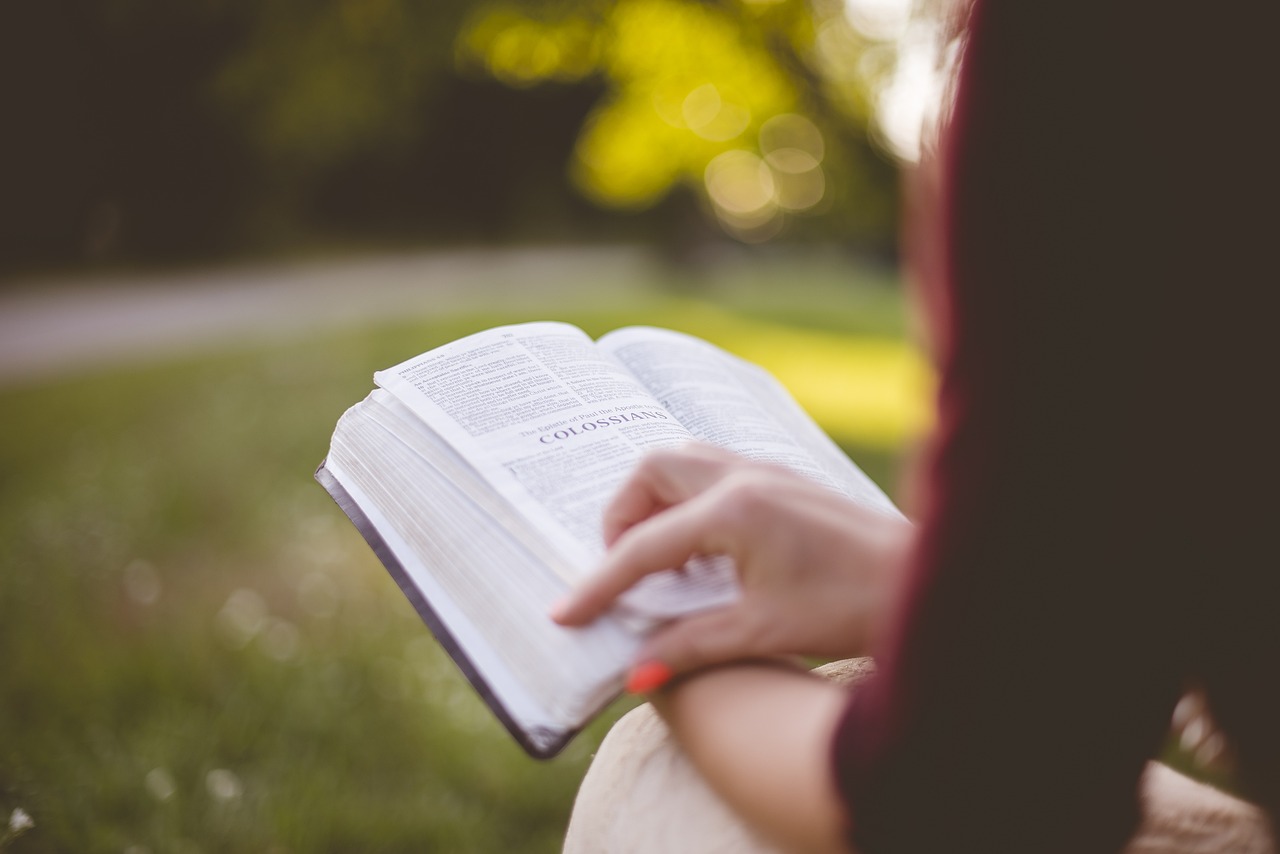

Even if you don’t pray the Liturgy of the Hours, these Antiphons may sound familiar. This is because they were incorporated into one of the best-known hymns of the Advent season: “O Come, O Come Emmanuel.”

Scripture:

-

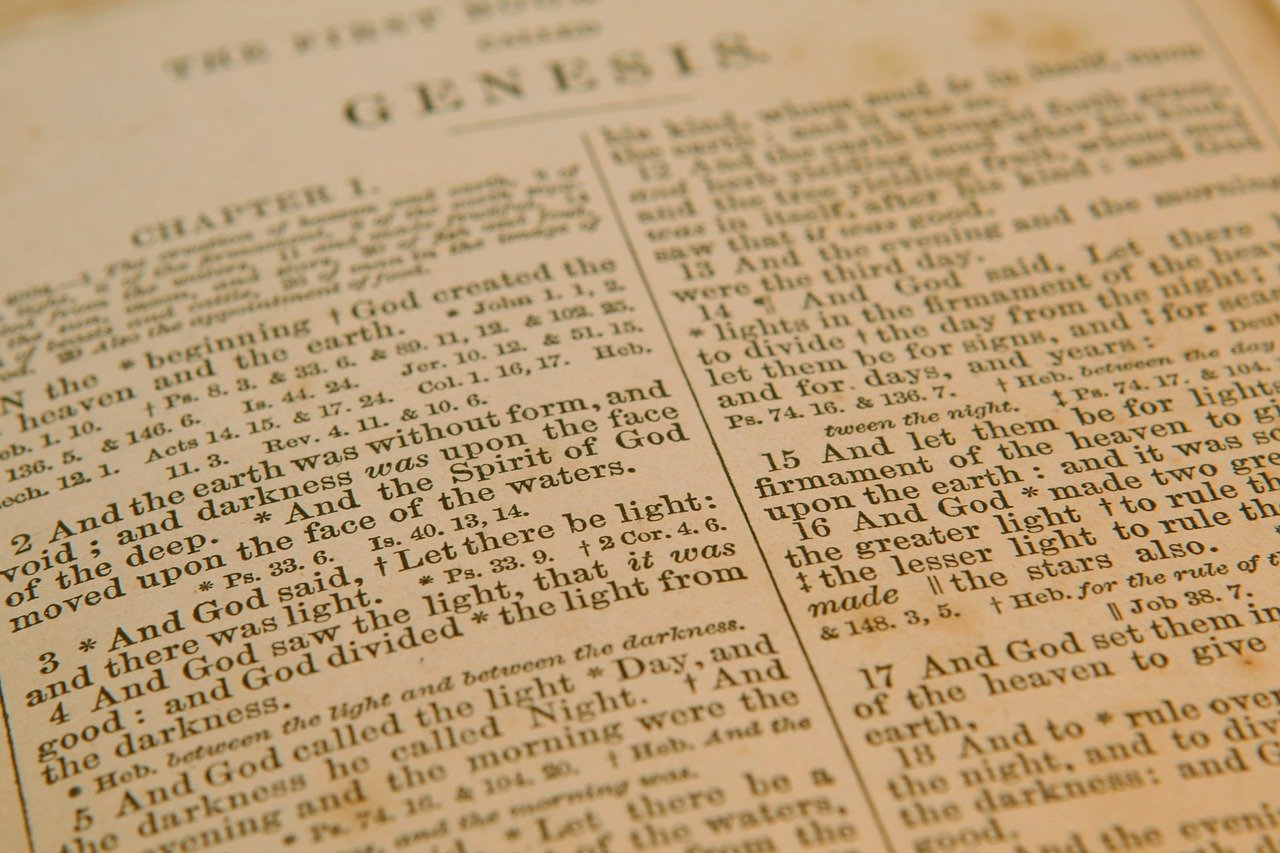

O Adonai or O Lord and Ruler: References Exodus 3:14 and Matthew 2:6, Micah 5:1, and 2 Samuel 5:2; describes how God appeared to Moses in the burning bush and gave him the Law on Mount Sinai.

-

O Radix Jesse or O Root of Jesse: References Isaiah 11:1, Isaiah 11:10, and Isaiah 52:15; describes how Jesse's stem was raised up as a sign for all peoples and that kings stood silent in his presence.

-

O Clavis David or O Key of David: References Isaiah 22:22 and Revelation 3:7; describes how the Key of David opens and no man closes, and closes and no man opens.

-

O Oriens or O Rising Dawn or Morning Star: References Jeremiah 23:5, Zechariah 3:8 and 6:12, Habakkuk 3:4, Wisdom 7:26, and Hebrews 1:3.

-

O Rex Gentium or O King of the Nations: References Jeremiah 10:7 and Haggai 2:7; describes how the King of the Gentiles is the Cornerstone that binds two into one.

-

O Emmanuel: References Isaiah 7:14, 8:8, and Luke 1:31-33; describes how Emmanuel is the King and Lawgiver.

Books: The Everyday Catholic's Guide to the Liturgy of the Hours, by Daria Sockey (Franciscan Media, 2013)