First, you can say that we believe that the bread and wine at Mass become the body and blood of Christ. Then add your own experience of encountering Real Presence, because, frankly, theological terms never get to the heart of the matter. No one comes to Jesus by means of a word like this.

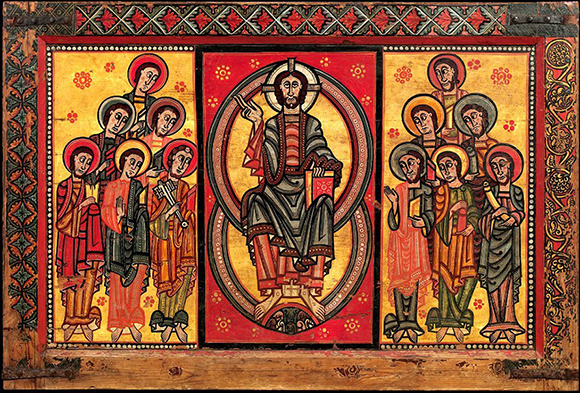

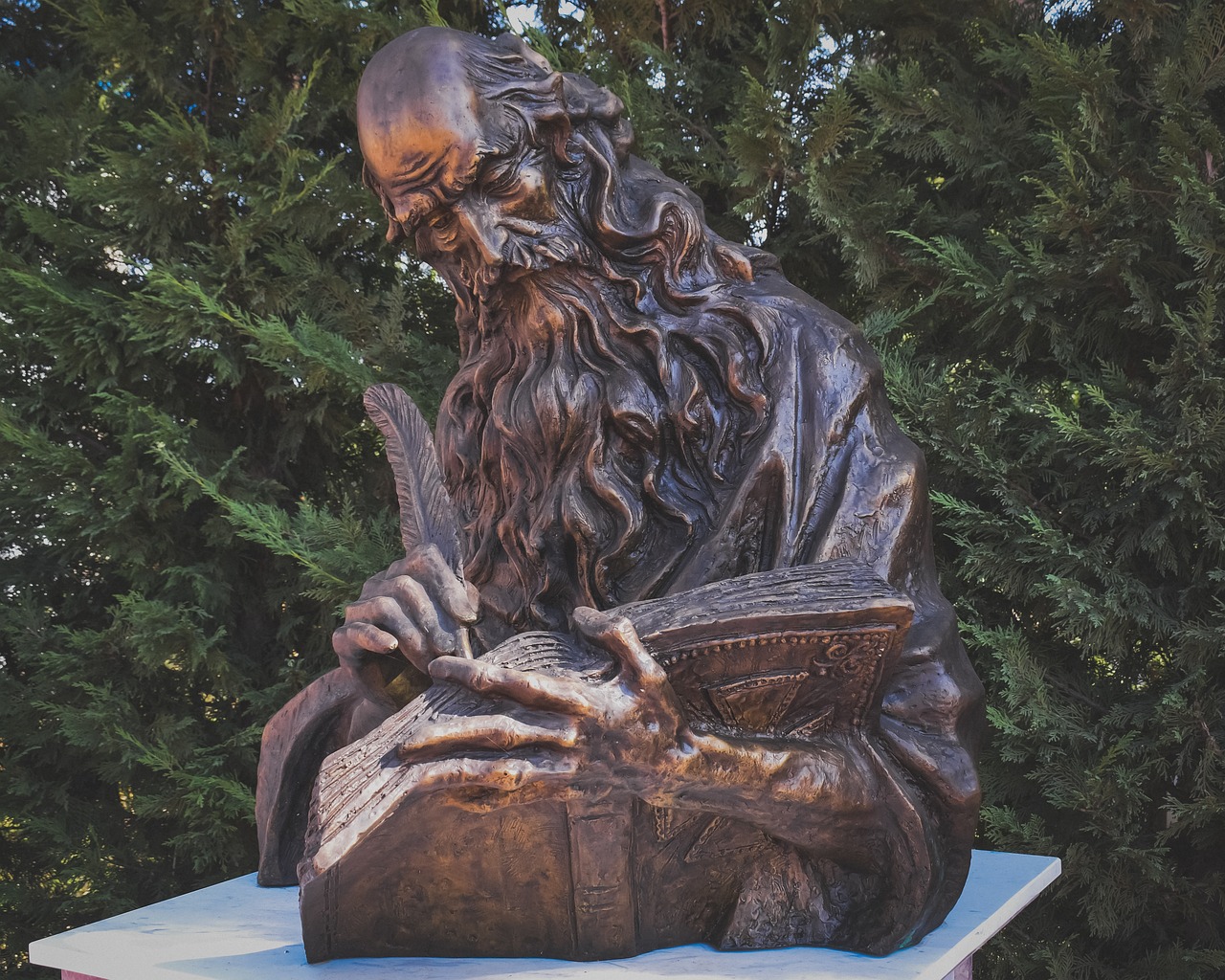

Why do we have this word? Medieval theologians sought to explain why our eyes see bread and wine, yet we claim Christ truly present. Peter Lombard described how the physical elements are transformed and only the “appearance” of bread and wine remain.

During the Protestant Reformation, Eucharist was hotly contested. Most Reformers viewed Eucharist as a memorial meal. In response, the Council of Trent defended an actual substantial change—transubstantiation—using Lombard’s interpretation. In other words: best not to define a mystery precisely, but allow God to work.

Twentieth-century theologians introduced two more words to the conversation. Transignification emphasizes changes in meanings rather than in form. Bread and wine normally mean nourishment. Consecrated bread and wine signify nourishment with Christ's life.

Transfinalization focuses on ultimate purpose or “finality.” Food and drink for the body gain a new goal as food for the spirit. Still, the most vital change remains what happens to us who receive it.

Scripture

• Matthew 26:26-29; Mark 14:22-25; Luke 22:14-20; John 6:22-59; 1 Corinthians 11:23-26

Online

• Mysterium Fidei, Encyclical of Pope Paul VI on the Holy Eucharist

• World Council of Churches, Unity: The Church and Its Mission, with links to documents including Baptism, Eucharist, and Ministry

• "Why do Christians believe Jesus is God incarnate?" by Alice Camille

Books

• 101 Questions & Answers on the Eucharist by Giles Dimock, O.P. (Paulist Press, 2006)

• The Eucharist: A Mystery of Faith, by Joseph M. Champlain (Paulist Press, 2005)

• The Eucharist and the Hunger of the World by Monika K. Hellwig (Paulist Press, 1976)