Priesthood in Roman Catholicism is rooted in two Old Testament images of priesthood. The first is the high priesthood of Moses' brother Aaron, which exercises three main responsibilities: worship and sacrifice, rendering the divine proclamation, and instruction of the people concerning divine law. The second image derives from God's covenant that names all of Israel a holy people, a royal priesthood. In the sacramental language of the church, the tri-fold leadership component of priesthood is bestowed with Holy Orders, while the corporate sense of priesthood springs from Baptism.

The Christian understanding of priesthood is grounded in Jesus, who is compared with the Levitical high priest in the exalted theology of the Letter to the Hebrews. First Peter also describes the church as a priesthood of believers. In the tradition of the early church, however, there were no individual priests to speak of. Perhaps the term seemed too confusing in a society already inhabited by Jewish and "pagan" priests. Instead, Christian leadership derived from the local bishop, who presided at Eucharist and provided guidance and governance. Each bishop was assisted by local presbyters, and as the church expanded territorially, the roles of presbyters stretched to include presiding at Eucharist. Priesthood, used at the end of the second century to describe the role of the bishop, gradually was extended to include the presbyterate. At this time episcopacy, presbyterate, and diaconate took on their normative divisions of responsibility.

After Constantine legalized Christianity in the 4th century, the orders of clergy took on a greater resemblance to hierarchies familiar to the Empire. Concurrently, the monastery phenomenon was growing in authority, and priesthood began to absorb the monastic ideal of separation from the lay state.

In medieval times, priesthood was increasingly identified with its liturgical powers in the Eucharist, minimizing its ministerial role and relationship to the community. After the Protestant Reformation rejected the non-biblical distinctions between clergy and laity, the Council of Trent (1545-63) upheld and strengthened them. The image of the Catholic priest was heavily reinforced in its distinctive character as the man set apart, both celibate and religious, who evokes the sacrifice of Christ in the actions of the liturgy and in his very being. It took a later Council, Vatican II, to reassert the dignity of the priesthood of the baptized, and to re-present priesthood as an extension of the bishop's pastoral ministry, locally expressed. The three-fold mission of preaching, sacramental ministry, and community leadership rebalanced the service of Holy Orders.

Scriptures: Exod 19:5-6; Deut 33:8-10; Letter to the Hebrews; 1 Pet 2:4-9

Books: The Theology of Priesthood - Donald Goergen, Ann Garrido, eds. (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2000)

Ministerial Priesthood in the Third Millennium - Ronald Witherup, et. al. (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2009)

To be exact, three days on the liturgical calendar honor buildings—and another celebrates a chair. Since most Catholics think of feast days as memorials of saints and martyrs, the notion of venerating places and furniture can sound more than a little odd.

To be exact, three days on the liturgical calendar honor buildings—and another celebrates a chair. Since most Catholics think of feast days as memorials of saints and martyrs, the notion of venerating places and furniture can sound more than a little odd.

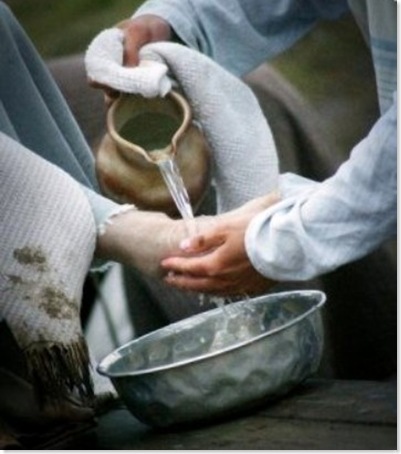

Humility is just about the exact opposite of everything you see in the world nowadays! Our 21st-century moxie is entirely egocentric. As the T-shirt says, "It's all about me." So to discover the essentials of humility, you have to experiment with self-emptying and change the channel from us to the Ultimate Other.

Humility is just about the exact opposite of everything you see in the world nowadays! Our 21st-century moxie is entirely egocentric. As the T-shirt says, "It's all about me." So to discover the essentials of humility, you have to experiment with self-emptying and change the channel from us to the Ultimate Other.